The Emerald Score: The Languages of Magic and Music

Today we’re spicing up our collection of longreads dedicated to specific themes and characters with a more abstract essay written by our associate, the leader of a smaragdcore band named «МКП №1» who goes by Dali Lama XXIII.

This short essay touches upon the origins of different reality programming languages, both magical and musical. The way such languages organize human cognitive activity, their syntax, their similarities and differences are infinitely rich and plentiful subjects, so this essay is just a gateway to the realm of these fascinating matters which we plan to report on in future.

As above, so below. This is one of the key maxims summarizing the way magic works. In other words, magic becomes effective because a mage believes in a certain connection between simple and complex matters, between local and global phenomena, between microcosm and macrocosm. This connection allows to act upon mundane objects (or even one’s own body) in the hope of bringing desired changes on a large, maybe even planetary/cosmic scale.

In terms of art, this description could be applied to the interactions between a piece of art and its audience (viewers, listeners, readers etc). Every piece of art (being a set of signals of some sort) is based upon some rules, follows some laws even if its author claims there were no rules involved in its creation; every choice regarding signals made by an author is always determined and limited by a certain cause.

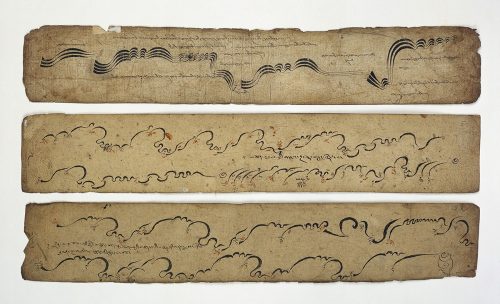

Let us consider music and its listeners now. For the music to really work its magic the listener should be duly trained. There is a common notion of «harmony»: music is assumed to be something «harmonious». There is some truth to this, but it should be noted that there is no such thing as universal harmony. Today harmony is typically interpreted as classical post-Greek Western harmony, with its tones and modes rooted in the realm of metaphysics. This kind of harmony, with Pythagoras among its chief developers, was literally magical at first: the «as above, so below» principle fully applied to it, with movements between tones corresponding to the movements of heavenly bodies and cosmic forces (Boethius and Kepler wrote about such harmony later, and the art of music composition was a staple of medieval classical education along with mathematics).

Generally speaking, for the art to work its magic upon us we should be able to decipher the foundational principle or idea behind a given piece of art above and then comply with it below. The simplest case of such magiс in action is being moved by a rhythm of a musical composition which somehow matches with one of the rhythms governing our life: you don’t have to believe in said rhythm or something like that, because all body processes naturally have their own rhythms that you can even observe in an anechoic chamber like John Cage did once.

However, to awaken to more complicated layers of a composition (and enjoy a deeper sort of mystical participation) one has to understand its author’s language to some degree, has to recognise the law upon which this composition is built. Hazrat Inayat Khan, for instance, writes in his tract upon music that a Hindu would always be uncomfortable with evening ragas performed in the morning; it’s really obvious that a citizen of Arkhangelsk who is unfamiliar with Indian music will miss that subtle detail, perceiving both morning and evening ragas as equally exotic.

Along with classical harmonies (systems of signal organization) nowadays we are treated to a multitude of nonclassical harmonies. In earlier times harmony was understood as some indisputable truth that lies at the heart of all Creation.

Postmodern philosophy proposes to accept manifoldness of possible truths: we are basically free to treat anything as truth, no matter the circumstances. This resonates with a notion that, as R. A. Wilson says, is a basis for the techniques of practical occultism (the art of «rapid brain change»): no external situation makes a mental state inevitable. So while every choice regarding signals made by an author still remains determined and limited by a certain cause, we enjoy the freedom to use our wits to reimagine this cause as we see fit.

Otherwise speaking, as long as you can formulate a meaning, there is one. In a sense, opening up to the magical side of music is similar to a progress on a path of becoming a master of any art; first you just follow the rhythm/copy what masters do, then you begin to understand the laws governing given musical piece/the laws of given art, and finally you discover a profound meaning unique to yourself/make your own improvements to the laws of your art.

Anyway, this leads to the increasing importance of the role of critics and commentators, to the increasing importance of presentational side of the art — and the process of teaching its possible audience corresponding systems of signal organization (or methods of crafting one’s own systems) so the art can work its magic upon the audience in full measure.

Conclusions? At present each case of outsider art essentially can be fitted to reach the general public, only it comes mostly at the cost of its message, which becomes hollowed out and dumbed down to allow untrained audience to experience mystical participation. To beat this prevailing order authors should probably make their art as prismatic/rhizomatic as possible, basing it upon existing traditions to a degree yet easily allowing a multitude of complex interpretations. Considering traditions, we should remember that there are no immutable traditions and artists constantly redefine and rerecall them. Finally, considering magic, the more languages you have a command of, the more your potential for magical actions, and languages of musical harmonies are no exception; here’s a reason for the authors to conduct artistic experiments.

Dali Lama XXIII

Дорогой читатель! Если ты обнаружил в тексте ошибку – то помоги нам её осознать и исправить, выделив её и нажав Ctrl+Enter.

Spelling error report

The following text will be sent to our editors: