Beyond Macumba: interview with Umbanda scholar

About six months ago we interviewed Russian practitioners of Quimbanda, a tradition still quite exotic for the post-soviet world. We promised you a review of Umbanda, another Afro-Caribbean tradition, which is closely linked to Quimbanda, being a sort of its right-hand twin. We, however, can split up the Afro-Caribbean cults between the Right-hand path and Left-hand path only provisionally. This is revealed in the interview given by the amazing Alex Minkin.

Alex Minkin is an independent scholar and social activist, focusing his research on Brazilian culture since 1996. He is the founder of Ticún Brasil, an innovative social justice NGO that implements educational, social and art projects in Rio de Janeiro, as well as Brazilian cultural events in New York since 2008. Originally from Moscow, Alex studied at Yeshiva University and the Portuguese Language Institute in New York. He also co-hosts new music project Extended Techniques, dedicated to under-explored contemporary classical and jazz music. Alex is currently working on a book Seven Waves of Umbanda that traces the religion’s origins and historical developments and overviews rituals, festivals, folklore, music and the role Umbanda plays in contemporary Brazilian culture and society. The book is based on field research in over a dozen temples, texts by leading Umbanda scholars from Brazil and the US, interviews, and original video footage.

The volume of this interview and its richness in information make it a one-of-a-kind research, and we are very thankful to Alex for answering our questions in such detail.

It is generally thought that the three pillars of Umbanda are Catholicism, Afro-Brazilian traditions, and Cardecist spiritism. Is it true? If yes, could you please tell us in more detail about the contribution of each of them, especially the last one?

Yes, Umbanda emerged in the early 20th century, at the same time as Samba, co-creating Brazilian identity based on the mix of Candomblé (where African traditional beliefs were combined with popular Brazilian Catholicism), European Kardecist Spiritism and romanticized indigenous elements. This fascinating religious movement must be experienced by every open minded spiritual traveler to Brazil. With lack of effective central religious authority, almost every individual Umbanda temple follows its unique theological route inside of Umbandas spectrum, so some are closer to Candomblé, while others to Kardecism. Later we’ll talk about several different directions that developed under the umbrella of Umbanda, but first let’s name some of the common elements.

Umbanda believes that spirits are incorporated in the body of a medium – someone who purportedly mediates communication between the world of the spirits and living human beings – in order to offer spiritual consultations and healing to the congregants. In Umbanda ceremonies, the medium enters the state of trance using bodily movements triggered by ritual music or, in other words, surrenders to the spirit while dancing. This act of spirit incorporation eradicates boundaries between the self (medium’s “regular” identity) and the other (the embodiment of a summoned spirit). The idea of mediumship comes from Candomblé, Kardecism and native Indian beliefs.

In both Candomblé and Umbanda every Orixá corresponds to a Christian saint (the phenomenon called Syncretism) and is traditionally celebrated on a date close to that of the saint’s day. Unlike in Candomblé, African deities (Orixás) associated with powerful forces of nature, such as wind, thunder and lightning normally do not possess mediums directly. Orixás are believed to be too powerful and supreme to visit every Umbanda temple, so they send vibrations with lower spirits. I was introduced to the religion in 2008 at the tiny Umbanda temple Tenda Espírita Vovó Maria Conga de Aruanda in Rio de Janeiro that in its practices gravitates towards Candomblé. In this video, the temple’s Pai Zezinho de Ogum celebrates Orixá Ogun that syncretized with Saint Gorge:

Each Orixá has own mythology as elaborate as those of the ancient Greek and Roman gods, unique dance postures and rhythms. This mythology comes to Umbanda from Candomblé, but, similar to Old Testament prophets in Christianity, while this foundation is there, it is not well known, stressed and studied. In Candomblé, only some of Orixás myths are narrated in the rituals through devotional songs. The most comprehensive expression of these characters is brought to life through ritual spirit possessions. With emphasis on oral tradition, ritual performance replaces scripture. Brazilian sociologist Rosa Barbara explains that “music is the communication between the medium and the Orixá, while the dance is the manifestation of the communication.» Similarly to Candomblé, body vibrations are embedded in the fabric of Umbanda – its service is appropriately called Gira, from the word gyrate.

The percussion (drums and clapping) is the main musical instrument in both traditions and is understood as ritualistic magical activators used to communicate with Orixás and other spiritual entities. These drums have been ceremoniously prepared and considered to be holy objects because they communicate with the Orixás, each invoked by the distinct rhythmic pattern. Drummers must undergo intensive training and special ceremonies in order to be allowed to play. Each medium has her own way to reenact her spirit through dance movements, and a unique way of speaking (for example spirits of Gypsies speak Portunhol, interspersing Portuguese with Spanish words). They use props, like a Gypsy tambourine, that remind the spirit of his earthy life. For an outsider who walks into Umbanda ceremony there’s may be a feeling of interactive theatrical (even vaudevillian) performance.

Popular Brazilian Catholicism is a key element of Afro-Brazilian religion and later inherited by Umbanda. Pre-Christian gods were repackaged and reworked under the surface of worshiping to Catholic saints. Although the Catholic religion is monotheistic, popularly it was expressed in Brazil as if it were a polytheism. Every saint had a role to play (i.e. Santa Lucia takes care the eyes and the vision, Santa Barbara helps with the lightning and hurricanes). In Umbanda and Candomblé Brazil saw the natural union of polytheistic African Orixás with disguised European paganism. In the words of leading Brazilian Religious scholar Reginaldo Prandi, ‘Our sea is the sea of Yemanja, the sea of the Christians is the sea of Nossa Senhora dos Navegantes …but it’s the same sea.’

Another building block of Umbanda – Spiritism (or Kardecism, after its founder Allan Kardec) began in France in the nineteenth century as philosophy and science. The methods of communication with the spirits emphasize rationality and could be proven through the deductive method inherited from science. In Brazil Spiritism added mystical and ritual layers and transformed itself into religion (one can say in a way similar to football and carnival). Now the country has the largest Spiritist community in the world.

Allan Kardec set foundations of Spiritism in 5 works: The Spirits” Book (1857), The Book of Mediums (1859), the Gospel According to Spiritism (1863), Heaven and Hell (1865) and Genesis (1868).

Spiritism managed to blend basics of Catholicism (charity), Buddhism (reincarnations) Darwinism (evolution) and fashionable 19th century esoteric beliefs from Emmanuel Swedenborg to Theosophy of Madame Blavatsky. Unlike in Catholicism, Christ is considered most evolved spirit and reincarnation leads to redemption in Kardecism. Similarly to Candomblé, Christianity was used to legitimize the ‘exotic’ religion in the eyes of Catholics. Just like Candomblé, early Kardecism was persecuted (its books were famously burned in Spain in 1861). In Brazil Kardecism was adopted by intellectuals, military and civil servants in the late 19th century, despite the Penal Code of 1890 classification of the religion as a crime. The neo- Christian message of charity became a huge hit among middle-class people in urban centers who could appreciate fashionable European esoteric texts. The atmosphere of Kardecist meetings resembles slightly a university seminar with students listening to readings and engaging with spiritual «speakers» gathered in a table.

Umbanda is an experiential religion of allowing yourself to open into mysteries of communicating with the spirits. You will not find any of Kardecist books (or any other books for that matter) in most of the temples. Kardecism however attempted to set the moral code in Umbanda, distinguishing it from more ethically ambivalent African religions. In fact some scholars consider Umbanda a popular form of Kardecism. In accordance with Kardec teachings the lower spirits are rewarded for their spiritual advice (known as charity) with the evolution along the reincarnation ladder. Heaven, hell and the devil do not exist on Kardecist horizon and there’s concept of free will.

In addition to some of the foundations set by its predecessors’ religions, Umbanda introduced uniquely Brazilian archetypical spirits that congregants can identify with and seek spiritual advice. The most common are elderly black slaves (Pretos Velhos) and indigenous people (Caboclos). The ceremonies also call for the spirits of rural cowboys from the north, Bahian migrants, urban outcasts (Exus), Gypsies, children and sages from the East.

Pretos Velhos in early Umbanda were the Christianized spirits that suffered a lot and came back to preach humility. These spirits often developed to more rebellious Black activists towards 21st century. Curiously, early Caboclos were less related to native Brazilian Indians, but rather inspired by popular nineteenth century depictions of North American Indians of the likes of Fennimore Cooper (even including typical headdress not found in South America). In some regional Umbanda variations, especially on the north of Brazil, Caboclos became closer connected with Amazonian traditions and often central to the ceremonies. All archetypes of Umbanda, oppressed during their lifetime, come back as powerful spirits in a way of symbolic inversion to teach the beauty of creation and the joy of living. In addition to connection to mediums ancestors, such spiritual practice has therapeutic effect for Brazilians practicing Umbanda to relieve the historical and often present traumas of discrimination and religious intolerance. By giving the oppressed central role of deities, Umbanda symbolically reverses established social order and heals collective traumas. Through focusing on the neglected and rejected elements of the society the religion is trying to repair the historical damage, empower the oppressed with spiritual force.

What was the relationship of Catholicism and Afro-Brazilian traditions in early XX century?

Before the Second Vatican Council in 1965, Catholic Church attempted little dialogue with other religions. Catholicism was especially intolerant to Afro-Brazilian religions because of the explicit ban to consult the dead. Catholic preachers in the early twentieth century condemned Candomblé and Umbanda healing practices as scams and fraud. Umbanda tried to appease the Christians by keeping Catholic saints to represent most of the Orixás and by de-Africanization of the rituals. It did not seem to convince Catholics – in 1946 the church sued Umbanda Federation of Sao Paulo for copyright violations by using Catholic images in the rituals. Catholics saw in Umbanda a threat to the church’s monopoly on religious revelation.

Most famously the conflict between the religions was depicted in 1962 film – Brazilian Cannes winner Pagador de Promessas (Keeper of the Promises). A villager, the film’s prototype, is making a promise to Orixá Yansa to carry a cross to the church of Santa Barbara, Yansa syncretic pair saint. The church priest rejects the offering.

The legal problems continued into our time. As recently as May 2014 a Brazilian judge decreed that Candomblé and Umbanda are not to be legally considered religions in Brazil anymore. This decision was later overturned following public protests. The country has changed and Umbanda is now widely accepted by Catholics as most Brazilian of religions. Presently the most powerful, intolerant and often violent adversary of Afro-Brazilian religions is the raising Pentecostal church that equals Orixás worship to paganism or worse.

Was Umbanda in any relation with positivist interpretations of animal magnetism, telekinesis, scientific experiments with automatic writing?

Reinaldo Bernardes Tavares, history professor at Federal University of Rio de Janeiro told me that studies of Parapsychology were not popular in Brazil in the early twentieth century and these phenomena were understood as products of the direct actions of spirits. Umbanda followers are still often not aware about these scientific developments – the most important is faith.

When and under what circumstances did Umbanda take the shape of an independent religion? In this respect, the year 1907, Rio de Janeiro, and a medium named Zélio Fernandino de Moraes are often mentioned – how did he end up creating a cult? Into what key streams did Umbanda eventually split? What are its main varieties as of now, and what are their specific features?

Umbanda officially began on November 15, 1908 in the Kardecist center in Niteroi, Rio de Janeiro. Zélio Fernandino de Moraes, a 17-year-old boy incorporated a spirit who identified himself as the Caboclo das Sete Encruzilhadas (Indian of the Seven Crossroads), a ‘lower’ spirit that was not allowed at the middle class Kardecist services.

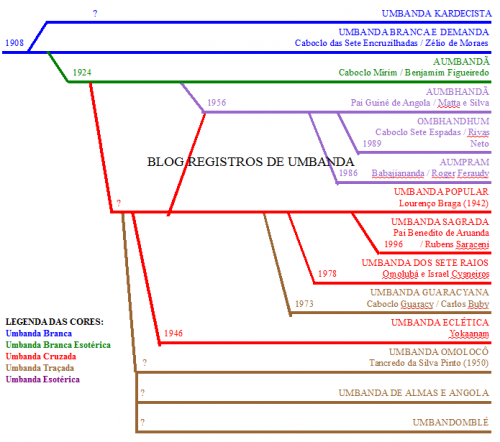

The diversity and richness of Umbanda is as striking as it is still unknown to the world. According to the research released in Spring 2014 by University of Rio de Janeiro, there are 114 distinct varieties of Afro-Brazilian religions, including different forms of Umbanda identified in the state of Rio alone, but it is estimated that there are over 300 types overall in the country.

As Zélio Fernandino de Moraes began the religion at the Kardecist center, White Umbanda temples that he founded closely follow doctrine of Spiritism. The centers are studying works of Alan Kardec and early Umbanda theologians, the mediums are only dressed in white and there is no use of African percussion (only clapping). The main entities who perform spiritual charity in White Umbanda are Caboclos, Pretos Velhos and children, there are no Exus and pombagiras and other Quimbanda entities and newer spirits and no animal sacrifices.

Many Afro-Brazilian religions started to call themselves Umbanda with or without adopting Umbanda theology and spirits (caboclos and pretos velhos) to avoid persecution in 20th century, since Umbanda became legalized much earlier than Candomblé. In the 1960s migration from the Northeast of Brazil brought significant number of Candomblé and other traditional Afro-Brazilian religions worshipers to the South. These factors resulted in most widespread form of Umbanda in Brazil called by researchers Popular or Crossed Umbanda (in a sense of crossing Umbanda and Afro-Brazilian religions), but commonly still known by a single word – Umbanda.

French film director Vincent Moon will be releasing dozens of poetic cine-essays on current day religious cults in Brazil next year, including few on Umbanda that we work together on.

Here’s his earlier film depicting Popular Umbanda ritual from the North of Brazil:

Popular Umbanda is most dynamic and responsive to the shifts in Brazilian society, adopting the mystical and religious practices that suit its congregants, adding spiritual entities (i.e. Baianos – Bahian migrants). This form of Umbanda is open to any spirit that wants, or needs to manifest itself. No discrimination by social, racial, religious or sexual base. ‘Umbanda reveals isomorphisms and similarities between so many cultures that it can be seen as exemplar of coexistence.’ says Mel Alexenberg, head of the Emuna College School of the Arts in Jerusalem in his “Educating artists for the future”.

Popular Umbanda is fully experiential and lacking the common doctrine or written scripture. The rituals are mostly conducted in Portuguese, but Orixás are often worshiped in a way similar to Afro- Brazilian religions. In some temples most bound to African traditions animal sacrifices may be offered; such centers are often classified by scholars as Umbandomblé.

The main entities who perform spiritual charity in Popular Umbanda include both Umbanda and Quimbanda spirits such as Caboclos, Pretos Velhos, the children, cowboys, Baianos, sailors, mermaids, gypsies, Exus, Pombagiras and Exus-Mirins. Regional variation may have its own entities not known in other parts of Brazil (such as 3 enchanted Turkish sisters in Belem). Mediums are wearing colorful dresses to represent their entities, not limiting themselves to white. Another variation of crossed tradition is Umbanda of Almas and Angolas popular in the south of Brazil. It is strongly grounded in African traditions and sometimes uses human bones in its rituals.

Various esoteric streams of Umbanda developed by charismatic mediums over the years. They are influenced by theosophy, astrology, medieval Christian interpretations of Kabbalah and other global occult schools. In Umbanda Mirim there is no worship of Catholic saints and Orixás are reinterpreted in a completely different way from African traditions. Eclectic Umbanda emphasizes Catholic side of syncretism. Aumpram attempted to legitimize Umbanda at the time of persecutions by distancing from its African origins. Aumpram’s scriptures written by Roger Feraudy trace Umbanda to lost mythical continents, Lemuria and Atlantis, which sunk into the ocean 700,000 years two. In these continents, the extraterrestrial beings taught locals the foundations of Umbanda – Aumpram, or the true divine law. Ombhandhum has similar myth of origins and also uses Indian mantras and Sanskrit. Aumbhandã is focusing on universal hidden language that relates astrological symbols, numerology, Kabbalah and the use of colors.

Popular contemporary stream called Sacred Umbanda emerged in São Paulo in 1996 with creation of Theological Academy of Umbanda. Well written theological and historical works by founding mediums Rubens Saraceni (i.e. The seven lines of Umbanda: the religion of mysteries) and Alexandre Cumino (i.e. History of Umbanda) are highly recommended for Umbanda students. Alexandre is also active in social media today with live broadcasts over his Facebook page. Sacred Umbanda seeks to be completely independent of Africanist, spiritualist, Catholic and esoteric doctrines while recognizing the influence of these religions.

Umbanda Guaracy is worth a special mention as it is most successful internationally with network of 14 temples in Brazil, Europe (Portugal, France, Austria, Switzerland, Belgium) and North America (California, New York, Washington and Canada). This movement was founded in São Paulo in 1973 by medium Sebastião Gomes de Souza better known as Carlos Buby who then received spirit of Caboclo Guaracy. There is no worship of Catholic saints and Orixás are interpreted close to African traditions. Guaracy is presently the only Umbanda temple in New York, so I had a chance to visit their small, but welcoming and warm community on several occasions. Some of the mediums speak English making introduction to Umbanda easier to most of the foreigners. Vast majority of the congregants are Brazilian umbandistas living in NY with few “gringo” Brazilophiles and spiritual seekers. Here is Carlos Buby at TED talk São Paulo:

Take a look at the chart of Umbanda development compiled by Brazilian scholar Renato Guimarães. The position of the branches in the graph does not indicate higher or lower hierarchy; the Umbanda streams are shown in the order of their appearance as well as some possible interrelations between them.

Absent from the chart is the newest star in Umbanda constellation – Umbandaime, mix of Umbanda with another syncretic Brazilian religion Santo Daime. Santo Daime mixes strong Folk Catholic foundation with elements of several religious or spiritual traditions such as Spiritism, African animism and indigenous South American shamanism. Native Indian brew Ayahuasca, referred to as Daime within the practice, which contains several psychoactive compounds, is drunk as part of the ceremony.

During the decades of authoritarian military dictatorship that ruled Brazil from mid-sixties to mid-eighties many artists and intellectuals joined hippie communities to reinvent society, art and spirituality. This period also coincided with global wave of counter-culture and spiritual renewal based on ancient religions. While Americans and Europeans drew inspiration for alternative lifestyles from India and Tibet, Brazilians had native mystical blend of Umbanda. Magic, music, dances and songs of Umbanda allowed its practitioners to escape from hypocrisy of the mainstream and provided tools for spiritual and artistic self-discovery and expression. Many artists were especially attracted by Umbandaime in their search for ecstasy, for mystical experience, for the trance of incorporation. Lucina, counter-culture singer and now a ritual drummer at community Flor da Montana in Lumiar, Rio de Janeiro, recalls how she first visited an Umbanda center. She says ‘It is wonderful to see the caboclo arrive and talk to you…and give you a blessing, because Umbanda is like an Intense Care Unit“

Last fall I visited Flor da Montanha for a day long ceremony. It is in this spectacular mountainous area with cloud forest and waterfalls where one of the first connections between Umbanda and Santo Daime was made in the early 1980s. In the course of the 8 + hours ceremony at Flor da Montanha the mediums and guests incorporated caboclos, pretos velhos, exus and, most amazingly, children – when everyone was acting out her inner child, rolling on the floor, running around with the pacifiers and acting really silly. Daime was offered throughout the day and several Santo Daime prayers were added to otherwise familiar Umbanda rituals.

As the British would say, it was my cup of tea (excuse the pun). Adding Ayahuasca to Umbanda reminded me of D.T. Suzuki words, “After enlightenment men are men and mountains are mountains, only one’s feet are a little off the ground.» While most of the attendees drank 1–2 glasses, for my friend and I (both trying Ayahuasca for the 1st time) nothing happened before the 3rd dose – then kaleidoscopic effects appeared, changing/enhancing our perceptions of the trance ritual dances.

First part of the ceremony was outdoors, with trance dancing first in the heat of the sun and then under the tropical pouring rain with white twirling dresses turning red from the soil.

I found Umbandaime to be a very creative reimagining of Umbanda rituals with original beautiful songs. The artistic community of Flor da Montanha with few professional actors and dancers made the incorporations so mesmerizing. And did I mention the delicious homemade honey bread?!

This is how my friend Lisa who attended the ceremony for the first time described her experience:

“the Ayahuasca had a great effect…I didn’t feel it as strong as I expected. but it was very powerful in a different way. For me the most intense moment was the «cleaning process» quite at the beginning, where we (everyone, who wanted) got cleaned from our negative energies. I felt not only very light and strong afterwards, but also at least 2 meters taller.And I had this strong sense that I want to be there for other people.

Also I experienced that I wanted to follow my impulses. Of course the mix with Umbanda was also very special…but at the same time quite overwhelming.

I was on the one hand focused on myself and my own feelings and on the other hand there was so much to watch (and it’s also not easy to understand what’s going on there all the time)…and I also felt emotions of others…you feel in general very connected – in a nice way, but there were also moments where it was a bit too much for me and I had to go out for a bit.”

I spoke with G. William Barnard, professor of religious studies at Southern Methodist University, Dallas who is currently working on a monograph of the Santo Daime. He agrees that Umbandaime is a highly potent fusion. Here’s brief article in English about his visit to the community:

Is it true that Umbanda is more institutionalized than Quimbanda? That it is more institutionalized and, despite the difference of its variations, the Spiritist Union of Umbanda in Brazil, formed by de Moraes in 1939, still in a sense supervises all Terreiros?

The Umbanda federations do exist and issues numerous proclamations, but try for example asking a regular practitioner about 7 Commandments of Umbanda (one of the federation inventions) and you get a puzzled look. More practical function of these federations is to defend Umbanda against the intolerance and persecution and fight for equal rights with other more mainstream religions. Brazilian legislation presently considers temples of all religions, including Umbanda a Non-governmental association making each of them independent.

This decentralization is inherited from Kardecism and Candomblé where every man is a medium, a channel of communication between the living and the spirits. Therefore, there is no Umbanda Pope-like figure, nor any kind of hierarchy in the religion.

To what extent does Umbanda take over from Candomblé? How is it associated with Candomblé now?

Until the 1960s Candomblé was exclusively black religion concentrated in the cities with large former slaves population such as Salvador, Sao Luis and Recife. Later several factors influenced its wider popularity in Brazil. On the one hand migration brought tens of thousands of Candomblé followers to the other parts of the country. On the other hand, during global counterculture movement middle and upper class Brazilians began to question European cultural values and discover Candomble as the most authentic form of Brazilian spirituality. The Candomble oral Orixás mythology began to be written down for the first time in Brazil by scholars like Reginaldo Prandi. His collection Mitologia dos Orixás became a bestseller and influenced major revival of Candomblé among the general population.

Candomblé created one of the foundations for Umbanda that at first attempted to reform it with Kardecist ethical values. so Umbanda attempted to reform Candomblé. As part of the makeover Umbanda added new central characters of preto velhos and caboclos and moved Orixás to the background. At the same time Umbanda was influencing Candomblé, most obviously in Candomblé de caboclo where new Umbanda spirits appear along with traditional Candomblé Orixás. As Brazilian society is becoming more tolerant to African religions, Candomblé is coming back to take more prominent role in Umbanda. Movement for Africanization of Candomblé tries to undo the syncretism with Catholicism. Parallel trends of Africanization of Umbanda and focus on Quimbanda characters are another indicators that ethics of older Afro-Brazilian religions make a strong come back.

Illustrations: photos by Bruno Morais (gira de exu from Tenda Espírita Caboclo Sete Flechas Pai Benedito Beira Mar) and Alex Minkin (Exu 1, Exu 2 from Tenda Espirita Vovó Maria Conga de Aruanda ), Zé Pilintra (man and woman) statues from Umbanda store at Mercadão de Madureira in Rio. Also cover of Reginaldo Prandi book of Candomblé mythology «Mitologia dos Orixás».

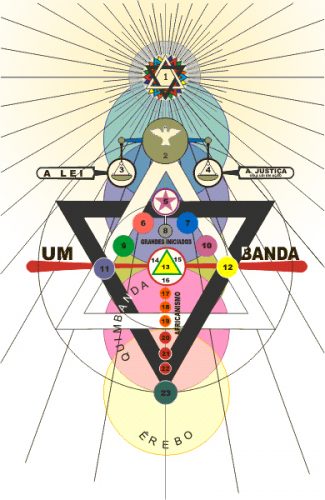

How is Umbanda associated with Quimbanda? What appeared first, what are the theoretical and practical demarcations of their differences? According to Umbanda and Quimbanda, do Exus belong to the Orixá, the manifestations of the supreme divinity Olodumareé? Could you tell more about the metaphysics and cosmogony of Umbanda?

Quimbanda is rooted in the same African religious traditions that formed Umbanda. It evolved from a hidden part of African side of Umbanda most of the 20th century to openly celebrated in the mainstream today. The central Quimbanda character Exu differs from a deity Orixá Exu in Candomblé, as he is a human spirit of an outcast, a criminal, a prostitute, a gravedigger – someone socially undesirable, the lowest in popular imagination. These spirits are believed to have the highest capacity to understand a common man, to offer a way around the daily troubles with work, money or personal life. They incorporate as joyful, party-loving creatures, joining congregants for a drink, or a smoke.

Up until the late 1980s Exus ceremonies were not publicly announced by the Umbanda temples that were afraid of backlash from the church and the government. With Catholicism losing its grip as we enter the 21st century, Quimbanda characters like Exus take central stage in ceremonies. More recently other spirits joined the Quimbanda’s ‘left’ side of Umbanda – sailors, gypsies and black migrants from the North of Brazil (Bahia).

One of my favorite Quimbanda spirits is Zé Pilintra, in a way a Brazilian Ostap Bender, tongue-in-cheek folkloric character from early Samba Rio times, famed by his extreme bohemianism and wild partying. Zé Pilintra song:

Theologically, Umbanda’s Exus are the messengers of all the Orixá, as they are undo the work of negative spells and help to revitalize all the sides of human existence. If you believe that your problems can not be solved by Caboclos, or Pretos Velhos, you appeal to Exus, who don’t draw clear line between good and evil. Just like its inspiration Orixá Exu from Candomblé, Exu of Umbanda is available for any, even morally ambiguous request, or question. In more Kardecist or Catholic Umbanda variations, there are Exus of light, or baptized Exus consistent with Christian ethics of the main Umbanda characters – Pretos Velhos and Caboclos.

The cartoon shows today’s preferences of Afro-Brazilian religions adherents: only few people are attending religious seminars and courses such as medium development, more come to demonstrations for the religious rights, but what everyone loves are the parties dedicated to exus and pomba giras (exu female counterparts). See for example the scenes from Exu party beautifully filmed at one of my favorite Umbanda temples in Rio – Tenda Espírita Caboclo Flecheiro in 2015.

As far as we know, the mechanism of reincarnation in Umbanda is quite peculiar: could you tell about it in more detail? Does Umbanda have any concept similar to karma? Is it true that some variations of Umbanda (AUMbanda, for instance) were influenced by dharmic religions? If yes, what was that influence?

Coming from Kardecism, reincarnation in Umbanda sees mortals as reincarnated spirits on Earth, whose ultimate purpose is to evolve. Death is just the passing of the soul into the world of the spirits, where one continues to evolve by doing charity work with living human beings. More Christian streams of Umbanda don’t believe in reincarnation, as afterlife is explained there in terms of heaven and hell with omnipotent God controlling everyone’s fate. According to Catholic faith, the soul is eternal and non-transformable and, depending on its earthly deeds, it’s directed to either heaven or hell. Finally, more African temples of Umbanda will not talk about neither reincarnation, nor heaven and hell; life after death is not well defined in Candomblé.

I reviewed the theory of Karma in several Umbanda sources and did not find notable differences from Kardecist views. This concept was not present in most of Umbanda variations I attended; it is more of a theoretical subject in some of the upper middle class theological Umbanda literature that accounts for a tiny segment of the religion. Portuguese does even not have a letter K, the concept is pretty foreign to most of the people.

Apart from Brazil, where else is Umbanda popular? Living in New York, you should be familiar mostly with American context. But if you could say something about Umbanda in Russia, CIS, or the Russian Internet, that would be very interesting.

Brazilian expats typically bring Umbanda with them. The largest number of Umbanda temples can be found in the neighboring Uruguay and Paraguay, Argentina (where current Pope once had an interfaith service with an Umbanda priest), Bolivia and Chile. A number of Brazilians of Japanese descent returned to Japan since 1980s. This migration resulted in new Umbanda entities created in Japan: doctors, Buddhist monks, and samurais. In the US with the largest Brazilian diaspora, there are several Umbanda Guaracy temples in NY, Florida, California and Washington DC. Guaracy also has centers in Canada, Portugal, France, Austria, Switzerland and Belgium.

There is also a phenomenon of non-Brazilians discovering Umbanda. Besides exoticism, music and magic that may explain initial interest, it has a very contemporary and universal appeal in its philosophy and rituals that explains the religion’s growing popularity in Europe. Umbanda’s deities are imperfect souls that understand problems of common men and try to evolve by helping them. These spirits are liberating and not judgmental. Unlike Catholicism with its clear distinction between Good and Evil, multipolar universe of Umbanda justifies various modes of human behavior as diverse as nature itself. Some of us may feel closer to Orixá of thunder (Xangô), while others to Orixá of forest (Oxossi); some may feel affinity to fresh and calm waters of the lake (Oxum), while others to stormy sea (Yemaja).

Another reason for Westerners to be drawn to Umbanda is its relatively accessible set of tools to develop a mediumship. Many people feel that they have mental disorders because they see or hear spirits, and have no idea how to channel these vibrations. Juliana Silva who runs a blog Umbanda in Europe from Lisbon, says that old school Kardecist center can’t be the right answer for everyone looking for communicate with spirits. In temples of Umbanda, more and more Europeans receive guidance to develop their mediumship, no matter what spirit comes to manifest itself. Many of these new umbandistas are finding peace, spiritual growth and moral satisfaction by offering spiritual charity to others.

In German city Cologne, Gabriele Hilgers leads such non-Brazilian Umbanda congregation. Gabrielle was born in Düsseldorf and discovered Umbanda when she was researching new religions around the world. During one of the meditations in India she felt an urge to learn Portuguese and come to Brazil for the first time to study Umbanda. «It’s a chance for us Germans, to live our truth at heart, a religion which has no dogmas. The temple received people from all over Germany and also from other neighboring countries,” she told in the interview to Spanish Newspaper El País. Just as in Japan, German mediums invoke the usual Brazilian Umbanda entities, but also work with archetypes of the local Celtic mythologies Druidry and Wicca. Today, hundreds of Germans attend Gabriele’s temple, which already ordained three new priests all of them born in Germany.

I am not familiar with Russian temples of Umbanda, but with ever increasing interest to Brazilian culture and imminent globalization it’s only a matter of time before RUmbanda takes off. Perhaps, entities of Gypsies may find themselves at home in Russia first, as there’s a deep affinity to Gypsy mysticism in Russian psyche.

In this video that I made at Tenda Caminho Cigano in Nilópolis, Rio de Janeiro we can see Umbanda’s representation of Gypsy spirits.

Ciganos, as Gypsy are known in both Portuguese and Russian, symbolize freedom, beauty and promise of better future. Magic, music, dancing and singing of Umbanda lead to alternate reality and provide its practitioners with tools for spiritual self-discovery.

Interview: Insect Buddha, Jnanavajra, Maya

Дорогой читатель! Если ты обнаружил в тексте ошибку – то помоги нам её осознать и исправить, выделив её и нажав Ctrl+Enter.

Spelling error report

The following text will be sent to our editors: